We live in the greatest country on the earth (apologies to our international clients). We are the freest democracy, the strongest economy, and arguably have the brightest future. We have 4 people coming into this country for every 1 person leaving[1]. We have more international patents-in-force than any other nation[2]. We make up 5% of the world’s population, yet produce almost 25% of the world’s GDP[3].

Yes, we have our problems. But, like Warren Buffet, I’m still convinced America’s best days are ahead of us[4]. For the pessimist, go read Abundance by Diamandis and Kotler. It may influence your thinking about how we handle some of our largest issues: health care, pollution, clean water, energy, and education.

So, who pays to govern all of this awesomeness? You do. I do. We do. Through a myriad of taxes – payroll tax, income tax, sales tax, property tax, estate tax, etc. For many of us, our largest cumulative expense over our lifetime will not be our mortgage or our cars or even our annual retirement savings – it will be our tax bill.

We then elect some of our fellow citizens to represent us at the different levels of government to collect these taxes and spend it according to our societal desires.

And how are they doing at this? Most all local municipal governments – city, county, state – must abide by a balanced budget each year. What does this mean? It’s simple – they can’t spend any more than they bring in via tax collections. Need more revenue to fund additional government programs? Raise taxes. Constituents say NO to your tax increase? Then stop spending. Really pretty simple. Most of us have to run our own households the same way.

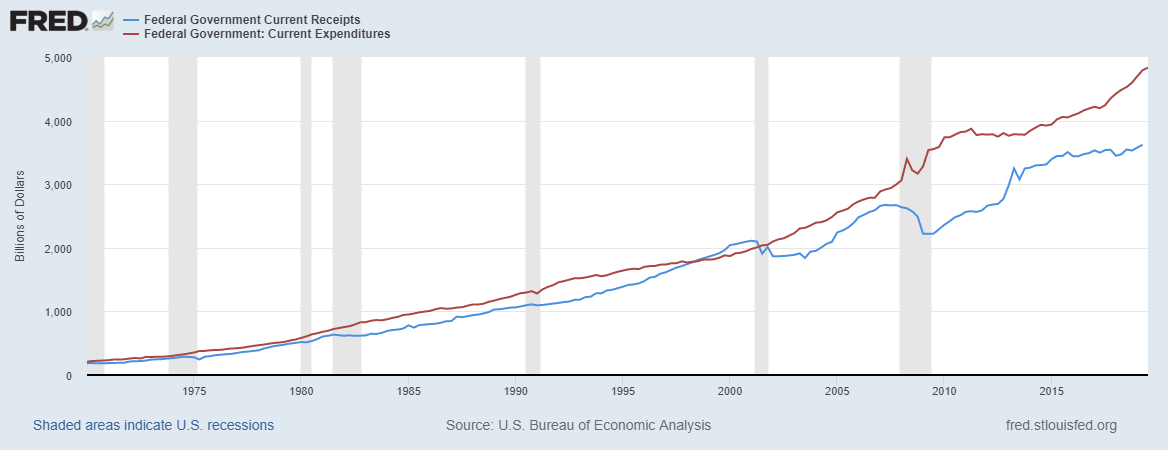

Our federal government, however, gets to play by an entirely different set of rules. They can spend more than they collect (we call this deficit-spending). And deficit-spend they do:

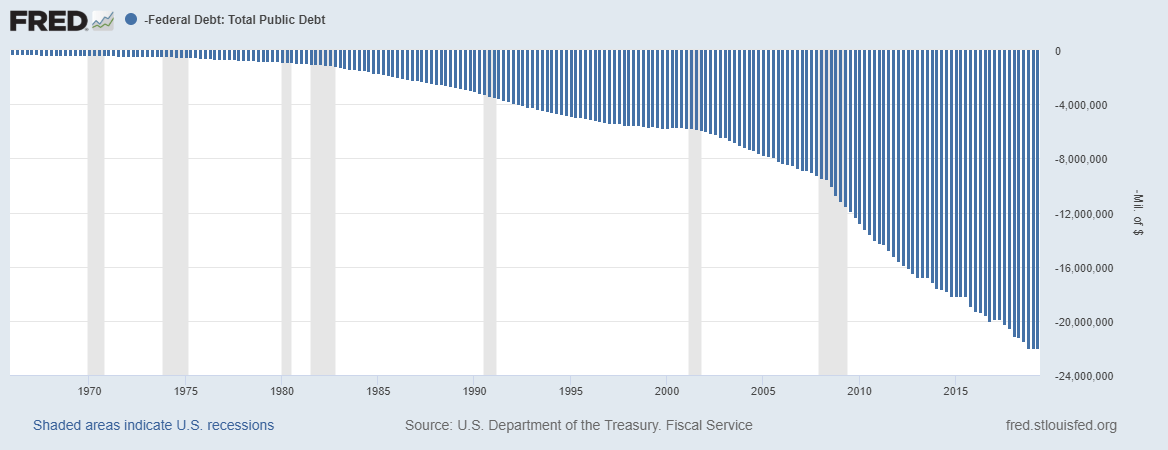

All this deficit-spending adds up after a while:

We currently have a gross national debt of approximately $22,023,283,000,000. Those are trillions; not billions, not millions – trillions. This equates to about $172,000 of national debt liability per household in the US.

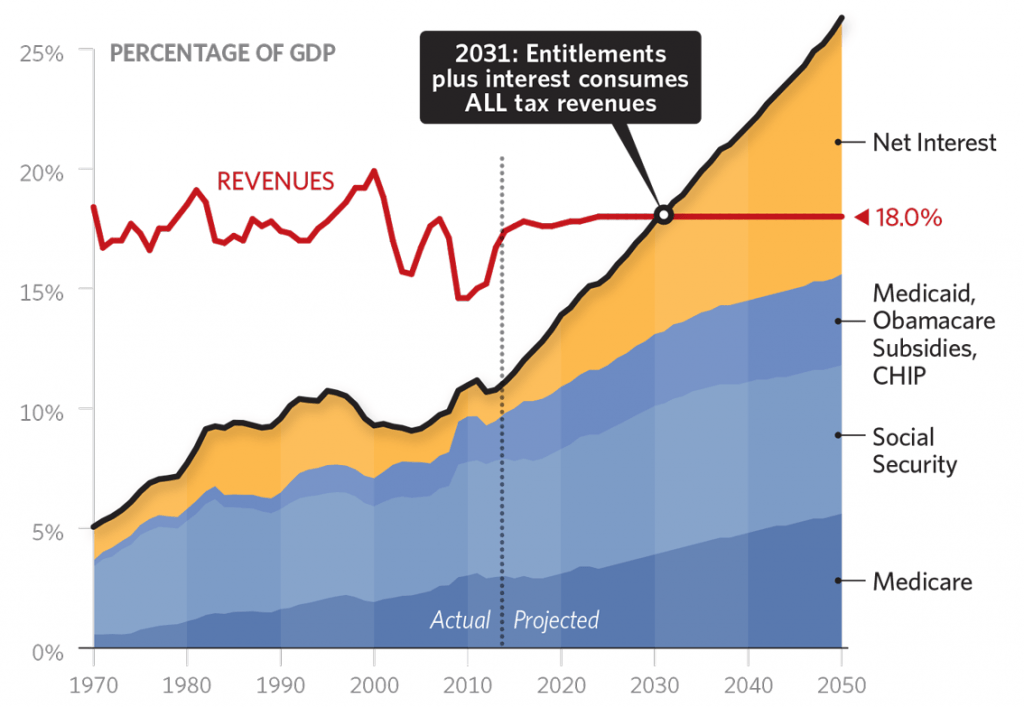

And the outlook isn’t much better:

Yes, you’re interpreting that correctly. By about 2031, Medicare, Social Security, Medicaid, and interest on our national debt will consume 100% of our projected tax revenue. This doesn’t leave much left over for our military, science, education, health, energy, agriculture, and every other federal government spending initiative, unless of course we want to keep piling it on the nation’s credit card.

I’m not very electable, but I do have a pretty good solution to fix this little debt problem of ours: RAISE TAXES, OR CUT SPENDING. Or both. It’s not magic. There really is no other way around it. Anything else is just smoke and mirrors. When you find yourself in a hole, the first thing to do is to stop digging.

But, instead of raising taxes or cutting spending, our elected Congress recently did just the opposite: they cut taxes and increased spending. There is a very academic argument to doing this (we’re all Keynesians now), but it will be awhile before it changes the trajectory of the graphs above.

Clearly, this isn’t sustainable. Eventually something has to give.

Furthermore, a recent survey found 7 in 10 millennials would favor a socialist President (4 in 10 for GenX, and 3 in 10 for baby-boomers and the silent generation). Before we dismiss the millennials, keep in mind millennials passed the baby-boomers back in 2014 as the largest generation in the US labor force, and they will pass baby-boomers as the nation’s largest living adult generation sometime next year at ~73 million strong. I won’t weigh in on the politics of socialism, but I will weigh in on the economics of it: anytime you have increased spending on social programs, you must increase the tax revenue to pay for it. There is no other way.

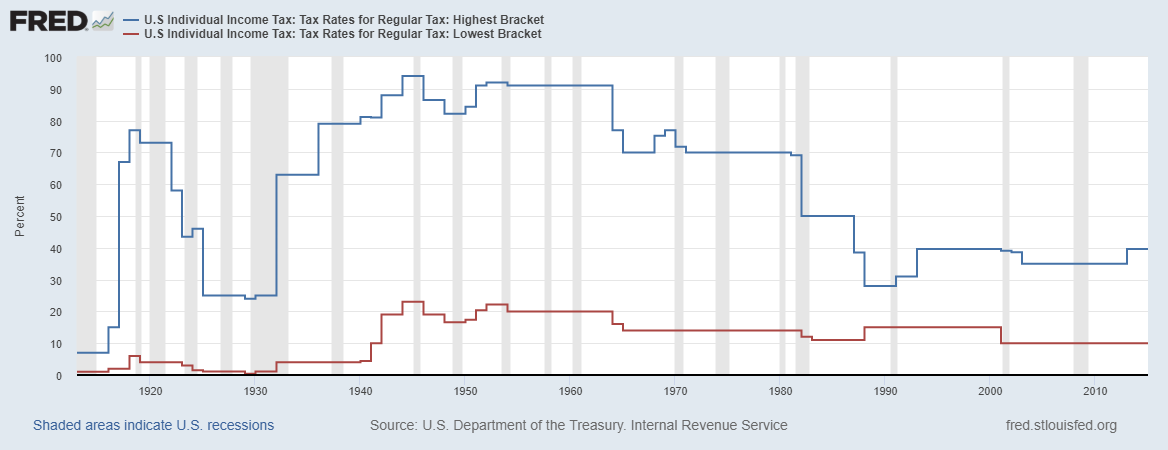

Now, before you say, “there is NO WAY taxes can possibly go any higher…” let’s go back in time a bit:

The blue line is the highest federal tax bracket, the red line is the lowest federal tax bracket. From 1936-1980, the top tax bracket was no less than 70% (!!!). But look specifically at the 50’s and early 60’s: If you were in the top tax bracket, 90% of every additional dollar you made went to Uncle Sam. Think about that for a minute. If you knew that of the next $1,000 you make, $900 of it would be transferred to the US Treasury, and then another chunk transferred to the state treasury, and only then did you get some, what is your motivation to go out and do the work to earn that next $1,000? Almost nil.

So yes, taxes can go back up.

Not only can they go back up, but I can tell you the exact date they will.

In order to get the recent tax bill passed, the Republicans had to agree to sunset the current round of tax cuts, with most all personal cuts expiring December 31, 2025. Starting January 1, 2026, tax rates will then revert to where they were in 2017. (Assuming we make it that far without any legislative change).

Look at the tax bracket chart above again one more time, especially the right end of the chart. With the exception of a brief period in the late 80’s, our current tax brackets are as low as they’ve been in 80+ years.

Put these two themes together – record high federal spending with no end in sight, and decades-low tax brackets with a known expiration date about 6 years from now – and this leads me to one central point: tax rates in the future are more likely to be higher than they are now.

Let me say this differently. Taxes are currently on sale. And just like all good sales, this one won’t go on forever. We have a window of opportunity between now and January 1, 2026 to be smart with our tax planning.

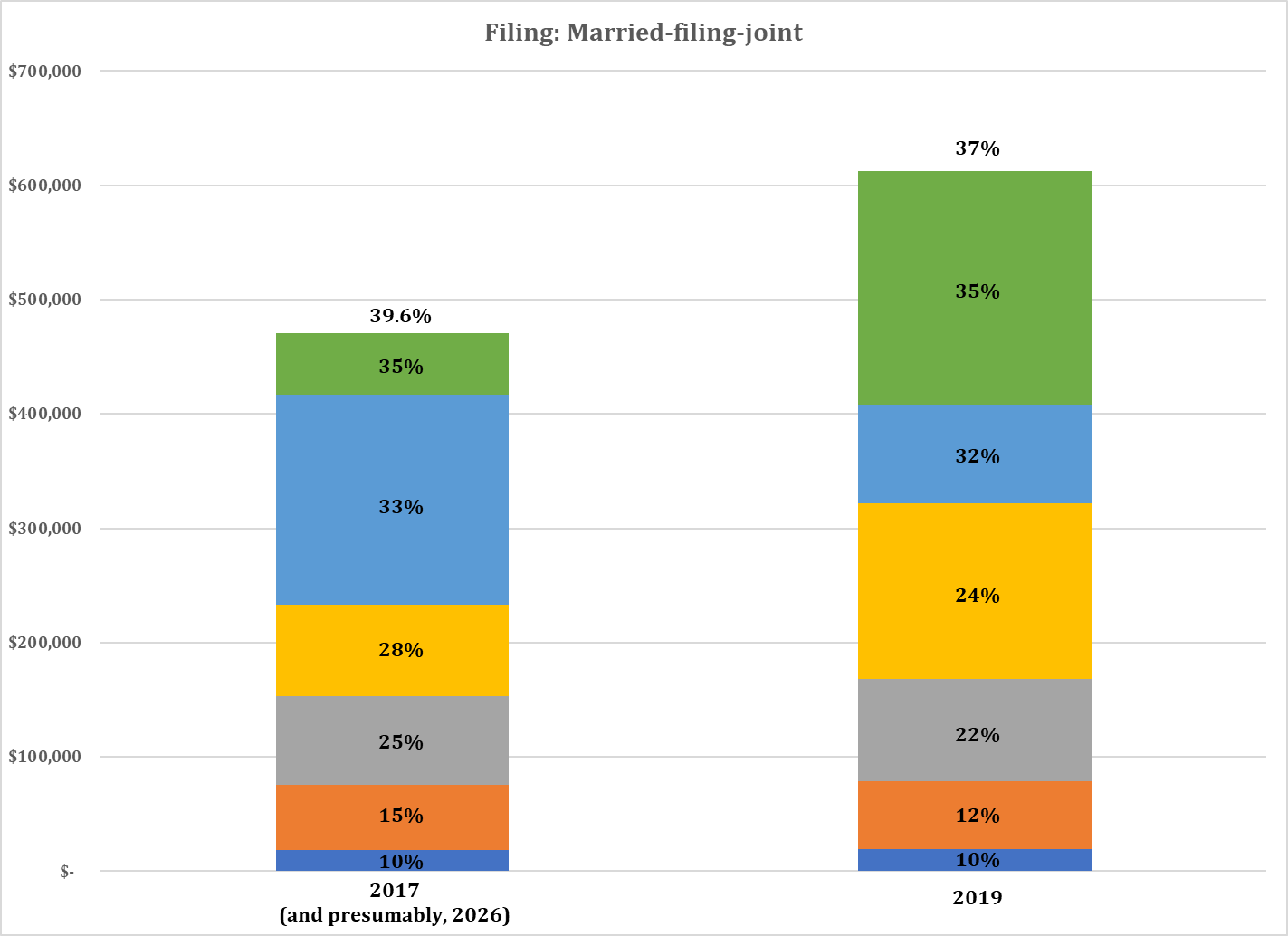

Simple case in point:

Let’s say a business owner files jointly with her spouse and has $200,000 of taxable income for the year:

In 2017, she had a federal income tax liability of $42,885 and had an effective federal tax rate of 21.4%.

Now, in 2019, with the exact same income, she will owe $36,349 (saved a cool $6,536, no big deal…) and have an effective federal income tax rate of 18.2%.

In 2026, her tax bill will go back to $42,885 and she will again have an effective federal tax rate of 21.4% (income numbers will probably be adjusted for inflation, but you get the point).

So, should our business owner go out and spend her $6,500 tax savings during this tax holiday? Sure! Uncle Sam is hoping she will.

But let’s run a scenario where our business owner has been diligently contributing to her 401k or IRA all along the way and now has a bunch of pre-tax money tied up in these account types. She knows she’s going to have to start pulling money out of these accounts at some point, if even only to satisfy her Required Minimum Distributions. If she knows she’s going to owe tax on that money at some point, shouldn’t she consider converting some of that 401k or IRA money to Roth money now at a lower tax rate? Probably.

One strategy would be to convert just enough of her pre-tax money to use up her new-found tax savings. So instead of taking the ~$6,500 tax savings, she would use it instead to pay the tax due on converting money from her IRA to a Roth IRA and making that money tax-free for the rest of forever. Quick calculations put this conversion amount for her somewhere around $27,000 this year without bumping her into a new bracket. In other words, if she did this right, she could convert ~$27,000 into tax-free Roth money in each year from 2019 through 2025 – somewhere around $190,000 by the time she’s done – all without raising her tax bill from what she paid in 2017.

This has two major long-term effects: she now has close to $200,000 that she’ll never pay tax on again, and it’s lowered the amount in her IRAs that will be subject to RMDs down the road. Being forced to take high-dollar RMDs down the road may keep you in an elevated tax bracket for the rest of your life.

This is just a simple example. I’m not saying you should do this, I’m just reiterating the point that we have a known window of time where a little proactive, smart tax-planning now could pay tremendous dividends down the road. If I know I have to pay the tax-man at some point, doesn’t it make sense to pay him when I’m in my lowest effective bracket?

So, what should I do about all this?

First, and foremost: pick up the phone and call your tax advisor. Get an appointment on his or her calendar sometime in the next couple weeks. Don’t wait until December. They just finished a brutal tax deadline a couple weeks ago and now have a short window of time for proactive 2020 tax planning before the end-of-year rush.

Ask them to project your tax situation out a couple years and see what makes sense now during this window.

Ask them how much headroom you have left in your current bracket before bumping into the next bracket. Ask them if it makes sense to recognize more of your income now and use up whatever headroom you have left at this lower bracket instead of recognizing it in a higher tax bracket in later tax years.

If converting pre-tax money to post-tax money makes sense, let’s do it a bit at a time over the next 6 years to keep you in a lower bracket instead of taking it all in one year and accidentally bumping you up into the next bracket.

Ask them what else they’d suggest to take advantage of this tax sale. If you’re a business owner, make sure you understand the new Qualified Business Income deduction. This new deduction alone may bring you back under certain income limitations that have phased you out before. Ask them what other features of the recent tax package you can take advantage of now before they expire in a couple years.

And if your current tax advisor “…doesn’t really do that sort of thing…”, we can connect you with one who will.

The last thing we want is to get to December 2025 and have you say, “Wait, why weren’t we talking about this 6 years ago?!?” A little smart tax-planning now could save us a lot in taxes down the road.

Let me conclude by quoting one of the most influential judges to have never made it to the Supreme Court, Judge Learned Hand, who has been quoted more often by the US Supreme Court than any other lower-court judge:

“…any one may so arrange his affairs that his taxes shall be as low as possible; he is not bound to choose that pattern which will best pay the Treasury; there is not even a patriotic duty to increase one’s taxes.”[5]

“…over and over again courts have said that there is nothing sinister in so arranging one’s affairs as to keep taxes as low as possible. Everybody does so, rich or poor; and all do right, for nobody owes any public duty to pay more than the law demands: taxes are enforced exactions, not voluntary contributions. To demand more in the name of morals is mere cant.”[6]